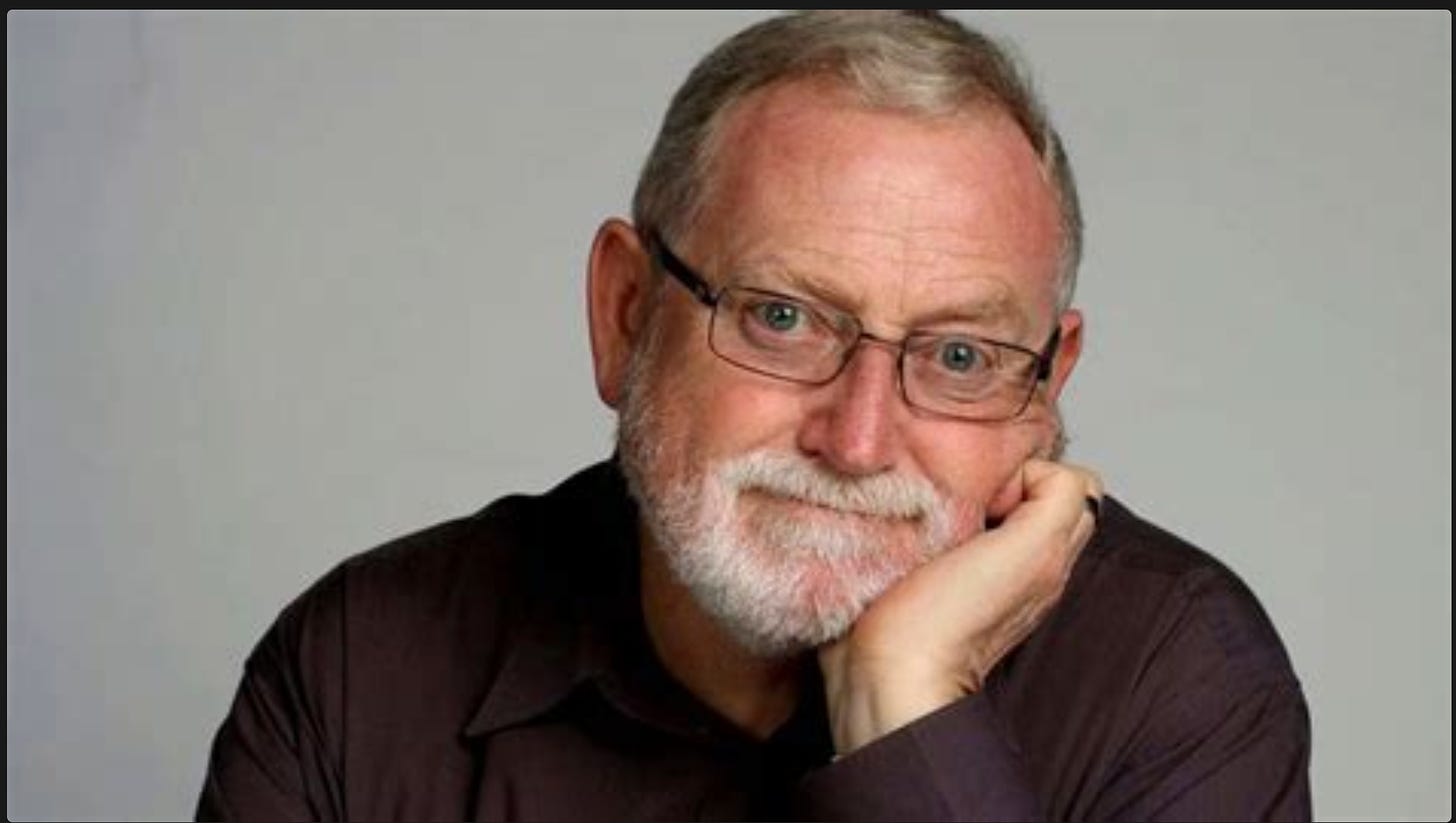

For quite a while I’ve been meaning to write a piece appreciating

Ross Gittins’ 50 year run as Australia’s leading economic journalist.

He’s one of the few who is neither an ideologue nor a recycler of

corporate talking points (no names, no pack drill, but most of my

readers will be able to think of plenty of examples).

This plan was pushed to the top of my agenda when Ross gave an exceptionally generous donation to support my Brissie to the Bay cycle ride in support of MS Queensland. It reminded me of the generosity of spirit Ross has displayed throughout his career.

Ross

started writing economic commentary for the Sydney Morning Herald in

1974, the year I started my undergraduate economics degree at ANU. So,

I’ve been in a position to follow his entire career, which coincides

almost exactly with the rise and fall of the ideology variously called

neoliberalism, market liberalism and economic rationalism.

Back in

the Whitlam era, “economic rationalist” wasn’t the pejorative term it

has now become; in fact, Whitlam saw himself as an economic rationalist.

As I wrote quite a while ago

‘Economic rationalism’

then referred to policy formulation on the basis of reasoned analysis,

as opposed to tradition, emotion and self-interest. With the exception

of support for free trade, there was no presumption in favour of

particular policy positions. The views of the first generation of

economic rationalists were generally in the economic mainstream of the

period — Keynesian in macro terms and supportive of the ‘mixed economy’

in micro terms.

Understood in those terms, Ross was, and remains an economic rationalist. But

During

the period of the Fraser and Hawke governments, both the intellectual

character and the theoretical and policy content of economic rationalism

changed. The critical and sceptical thinking that characterised the

first phase of economic rationalism was gradually replaced by a

dogmatic, indeed, quasi-religious, faith in market forces and the

private sector

Unlike many others, Ross did not

follow this path. Instead, he reacted against it, looking for an

understanding of economics that was more realistic and humane. This has

been a consistent feature of his later writing. Ross has regularly

criticised models of economic behavior based on narrowly defined self

interest and promoted richer models of people’s goals and motivation.

The

other thing I appreciate most about Ross is his willingness to engage

with the academic economics profession, rather than taking talking

points from corporate and bank economists, like so many other economic

journalists. I particularly remember his description of the late Fred

Gruen as a ‘useful economist’, that is, one who made serious

contributions to Australian public policy rather than focusing on

high-status publications in international journals.

I’ve always

aspired to follow in Fred’s footsteps in this regard, though I found it

necessary to do the international journal stuff as well in order to

maintain credibility while pushing leftwing policy views.

More generally, Ross has regularly picked up interesting work by academic economists and explained it to his readers.

Finally,

I’ve always found Ross to be a friendly and supportive person. As I

mentioned already, he demonstrated this again with a very generous

donation to sponsor my Brissie to the Bay ride for MS Queensland.

It’s been a great 50 years for Ross, and I hope for a decade or two more before he, and I, leave the economics scene.