Another Message Board

Post comments on any topic. Civil discussion and no coarse language please. Side discussions and idees fixes to the sandpits, please.

I’ve moved my irregular email news from Mailchimp to Substack. You can read it here. You can also follow me on Twitter @JohnQuiggin

I’m also trying out Substack as a blogging platform. For the moment, I’ll post both at this blog and on Substack.

The use of monetary policy as a blunt weapon of macroeconomic management may be an inefficient approach. To stun markets with high interest rates seems to be a strange way to try to lower inflation in the twenty-first century. When this policy option was first used there was less use of personal credit options. Today household debt is much higher as a proportion of personal wealth. Also in business more de t finance is being used. So when the RBA raised the cash rate on t he money market it is causing the cost of credit to rise AND the servicing costs of existing debt. This adds to cost inflationary pressures. Demand pull inflation may be tamed by raising official interest rates but cost push inflation may be adversely affected. Then there is imported inflation. This is Unlikely to be affected by the setting of Australia’s cash rate. In fact if the domestic cash rate is set too high too quickly it may even adversely affect attempts to reign in imported inflation. A new approach to containing domestic inflationary outcomes appears to be warranted.

The RBA Governor now no longer targets high nominal wage increases – he prefers numbers with a 3 in front of them rather than a 5,

“Philip Lowe has sent a polite but unmistakable warning to the Albanese government and unions that workers must accept temporary real wage cuts to avoid a 1970s-style wage-price spiral and to stop higher unemployment.

The Reserve Bank of Australia governor says that economy-wide wage increases of up to 3.5 per cent are sustainable, but pay rises should not “mechanically” match the inflation rate, which is now forecast by the bank to hit 7 per cent late this year.”

“We can have increases in some parts of the labour market bigger than that for a short period of time. But if wage increases become common in the 4 and 5 per cent range … then it’s going to be harder to return inflation to 2½ per cent.

There, we’re in a world where the economy will have to slow more, and perhaps the unemployment rate would need to rise.”

https://www.afr.com/policy/economy/pay-rises-should-start-with-a-3-to-avoid-inflation-spiral-20220621-p5avdp

A string of annual 3.5% pay rises for the lowest paid might be acceptable from this point. Let’s see how things go.

Special offer on zombie stakes

I finally got round to buying and reading JQ’s “zombie economics” book. It holds up well, as Keynesian pragmatism has done more generally in the two major crises since it was published, the covid pandemic and the Ukraine war. It’s in the nature of zombies that they will come to pseudo-life again, so it’s worth updating the cases against them as handy sharpened stakes. In this spirit, I spotted a possible gap in the debunking of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH for short).

EMH claims that the set of asset prices generated by free and liquid financial markets are the best possible at any given time, as they represent an informed collective judgement of profitability and risk. It’s plausible that the individual investors and traders whose buying and selling sets the price of an asset, say shares in Tesla, do make such judgements, in many cases informed by information about both aspects. (We’ll forget for now about speculators driven by noise.)

Now here’s the snag. The share price is one number, and the separate information about profitability and risk is not aggregated but irretrievably lost in the one-dimensional trading price. Any prospective investor or disinvestor in the asset has to make their own judgement about the two aspects. The market price may be helpful in this, but it’s not dispositive. In what sense, then, can the market price represent a collective wisdom?

Let’s make the standard assumption that investors are as a class averse to risk. So higher risk in one asset – stylised as the variance of expected profits – requires higher mean expected profits to compensate, and equate to a safer asset with lower expected yield. Still, investors vary in their tolerance of risk, and a random investor will normally disagree with the market over it, even if he (gender bias intended) agrees over profitability.

In a fairytale complete competitive model, it might be possible (the question is beyond me) to supply the lost information from derivative markets. But whether or not this is possible in Arrow-Debreu-Disney land, these comprehensive complementary markets do not exist in the real world, the one that EMH makes claims about. A more realistic ploy for the EMH is to take the average of investors, as the disagreements on risk cancel out. What cannot be rescued is the claim that the public interest is aligned with the private interest of the average investor. Externalities, which in the case of climate change are clearly risks, are real, large and cannot be assumed away.

Another striking case is that of shortages and gluts arising from general over- or under-production of particular commodities. For an individual company, a global shortage of its products leads to windfall profits, good news. Similarly a glut is bad news as it lower profits, though the lower prices benefit consumers and the excess supply may be collectively useful insurance against shortages, as in the Biblical story of Joseph and the Egyptian grain harvest. Shortages are not a trivial problem, to be assumed away thanks to the magic of the “free market”. We have recently seen their impact in a variety of important markets, from weapons and ammunition to computer chips, wheat, oil and gas, lithium and vaccines.

There is every reason to think that a rational government will have a very different view of many commercial risks than those held by participants in financial markets, and will not be bound by the EMH.

This line of argument might lend itself to formal economic modelling, and could be a worthwhile precautionary investment.

Now even Labor endorses the necessity of a real wage cut. Accepting the inevitable even if the unions do not:

“The Albanese government accepted workers might need to take a real wage cut to prevent high inflation from getting entrenched, after Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe warned against common pay rises of 4 to 5 per cent. Unions rejected the idea and said they would continue to push for annual pay rises of 5 to 6 per cent in negotiations with employers, putting them at odds with the government and the central bank.”

The unions here institutionalising the idea that they will pursue a wage-price spiral as a mastter of policy. And they are key funders of Labor.

https://www.afr.com/policy/economy/labor-bows-to-rba-real-wage-cut-20220622-p5avs1

Harry,

What about the profits spiral? What about profit push inflation? What about the rich who pay low or no taxes? You never seem to address these issues. [1] Please add some balance to your commentary instead of endlessly hammering working people, wage rises and wage push inflation only: wanting to make workers bear the whole cost of inflation fighting. The economy is a complex system with multiple moving parts. You ever only want to talk about one part. Why?

Note 1. – I grant that you addressed the issue of employers getting away with keeping non-legal amounts of job keeper payments and not paying them back.

Iconoclast, I am not hammering them but using economic reasoning to analyse the consequences of high sustained money wage increases. As I have said before – you are so blinded by your ideology and your normative views that you seem unable to sort out a positive argument – one that looks at the consequences of what will happen rather than making a moral argument about everything. Everything to you is a moral argument. Being concerned with the welfare of workers does not mean supporting high money wage increases (that the unions now say will be sustained) because this will necessitate a more severe monetary policy stance that is currently on the cards. This will generate unemployment and increased human misery.

Harry Clarke,

Both Professor John Quiggin (implicitly) and Professor Ernestine Gross (explicitly) disagree with your simplistic Econ 101 and hence with your very normative economics. They are both more accredited economists than you are. Their arguments are also clearly more complex, nuanced and empirically referenced than yours are. As both a sciences and humanities tertiary educated person and also having had extensive working life experience as a bank clerical worker, laborer, plant operator, farm worker, government clerical worker and computer systems support worker, I know a thing or too about real life at multiple working class levels, at multiple levels of production and social reproduction and at multiple levels of intellectual work. Aspects you clearly lack or at least fail to make operative in your thinking.

I find the general theories of Quiggin and Gross (to name two of many I have read and/or debated with on blogs) to be considerably more congruent with social and (hard science) empirical realities than the simplistic, normative, ideological, neoliberal, market fundamentalist position you present. I will take no lessons in economism from you, mate!

Profits will increase about 15% this year, in real terms. Wages will likely decrease, as they have done for the last 10 or so years. The attitude that we need to be very very worried about the latter not declining fast enough – rather than the former exploding into the stratosphere again, and again and again year on year, decade on decade – reflects an attitude that has driven the economy for about 30 years and hasn’t worked.

For every dollar of value produced in the economy, about 50 cents goes to a person who works for a living and the other 50 cents goes to someone who owns for a living, a record low in the last half-century. (This is down from about 65/35 in the 70s and is, incredibly, lower than the US). The profit share of the economy, by the way, is largely dominated by the non-productive banking/housing sector, unproductive assets, and international mining firms – this is just money transferred off workers, not new and better or cheaper products.

This economic system is not working. 30 years of taking money off working people and giving it to owning people has not led to a more productive economy, just poorer people. How about we try it the other way around for 30 years and see how that goes.

“Notice the panic about a possible ‘wage-price spiral’ in talk about inflation, and paying people more. No talk at all for the past 30 years of capital-price spirals, in housing for example. That’s good inflation, because it enriches the right (rich) people.” – Dr Henry Madison, Twitter.

Just this once, let’s listen to Milton Friedman. The current worldwide bout of inflation is not a wage-price spiral, since real wages are falling. That leaves “too

much money chasing too few goods”. The money side of this comes from everybody piling up cash savings during the pandemic. Solution: confiscation or forced freezing of excess bank balances. The goods side comes from the disruption of the pandemic including a reset of work-life balances, and Mr. Putin’s war. Solutions: defeat Putin, rebuild supply chains, patience. Only the last two look feasible.

So often, when we discuss economics, we are like the blind men meeting the elephant. We fixate on the first thing we touch. There are multiple causes of the current inflation. There are also multiple aspects to be concerned about in the current political economy. But since inflation appears to be very easy to grasp (it isn’t) we assume it must be very easy to fix and that fixing it will fix everything else.

andymessenger1’s post above and a link I posted a while ago (to Blair Fix on differential inflation) have pointed out that there are multiple inflations (and deflations) occurring at the same time. andymessenger1 has pointed out the long term shift in the Australian economy from wage income to profit income. Inflation is everywhere a redistributional phenomenon because of the differential inflation rates.

Nobody on the right wants to talk about distribution or redistribution or equality because they are perfectly happy with great inequality in our system and they want to (essentially) permit it or even facilitate it to get worse and worse.

andymessenger1’s post also illustrates the dangers of truncating a graph to the left: that is truncating the time series into the past, and only looking at economic history since “5 minutes ago”. Only a graph running from about 1970 to the current day can show the large, long term decline in the wage share of the economy compared to the profit share.

This is not necessarily raised to turn the clock back. It might not be necessary to greatly raise the wage share of the economy, though some rise appears necessary. It might be necessary to raise/institute wealth taxes and estate taxes, for example. It might be necessary to raise the public investment share of the economy over the hiding of wealth in tax havens. It might be necessary to raise the social wage (access to free public goods and services).

What won’t work is pretending this worsening wealth divide under neoliberal market fundamentalism is sustainable.

That’s right: the wage profit split is even worse if you consider inequality WITHIN the wage earning section of society. A builders labourer is paid a far smaller proportion of the income of a surgeon – or a failing chief executive officer – today compared to their counterparts in 1972. So even within what I would call the working class – people who work for a living, rather than owning for a living – far less of the smaller pie is going to the poorer end than it was 50 years ago. This is not because rich people are working harder or more efficiently and adding more value than their parents; they are simply taking money and keeping it and what are you going to do about it.

I think the wage profit split is the bigger issue personally but both problems are problems.

Nor is the problem inequality. The problem is laziness. That is an unproductive society.

JQ, perhaps a “Consequences of Inequality due to the Pandemic” Conference.

A version of “Inequality of Opportunity Conference”

2019″

…which seems to have been Cancelled due to “The speaker, Professor John Roemer, was involved in a hiking accident and he is unable to travel to Australia at this time.”

Pandemic initial conditions and policies

… exacerbate …

Inequality of Opportunity,

… the measure of which seems to be plagued by bad data and bias. See JQ, Cowan, etc below since 2012. The Covid ‘natural experiment’ Pandemic has provided stark outcomes and data to analyze, hopefully to settle measurement, solutions and policies to remedy Inequality of Opportunity.

I note even Sweden is not immune from recreating greater Inequality of Opportunity.

*

Nature today:

“Inequality researcher Francisco Ferreira explores the evidence that unfair circumstances affect people’s lives. He proposes that better data and new machine-learning techniques could help to quantify the true effect of factors over which individuals have no control. (Nature | 12 min read)”

“Not all inequalities are alike

“Better data and new statistical techniques could enable researchers to measure the form of inequality that seems most harmful to society — inequality of opportunity.

…

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-01682-3

*

“How COVID has deepened inequality — in six stark graphics

“Troubling data show how the pandemic has exacted an unequal toll, pushing tens of millions into poverty and having the greatest effects on already-disadvantaged groups.”

…

https://www.nature.com/immersive/d41586-022-01647-6/index.html

*

Lane Kenworthy post with links to relevant actors JQ, Cowan etc re:

“Inequality, mobility, opportunity”

…

“Is it possible, then, for a country to have high income inequality but also low inequality of opportunity? John Quiggin is skeptical. He suggests the UK experience has debunked this “third way” notion”…

https://lanekenworthy.net/2012/01/31/inequality-mobility-opportunity/

*

JQ working it out, with links to relevant actors etc re:

“Social democracy and equal opportunity

by JOHN QUIGGIN

on JANUARY 29, 2012

“My critique of Tyler Cowen’s post arguing the unimportance of social mobility has started off, or maybe merged into, of those old-fashioned blog firestorms we used to have back in the day, now also reticulated through Twitter – a few links here, here andhere. But rather than criticise Cowen further, I thought I would try to work through the bigger issues involved from a social democratic perspective[1]. In particular, as discussed in comments here, should social democrats favor policies to enhance social mobility, or does mobility between generations make inequality even worse, for example by justifying what appears as meritocracy?

“It’s helpful to start with some facts, and the big one is that inequality of opportunity and inequality of incomes (or, more generally) outcomes are strongly positively correlated. The US and UK are notable as being highly unequal societies in both respects. More precisely, as would be expected on the basis of even momentary thinking about the ways in which parents try to help their children, highly unequal outcomes in one generation are negatively correlated with intergenerational mobility in the next.”

….

https://crookedtimber.org/2012/01/29/social-democracy-and-equal-opportunity/

*

Ikonoclast, Labor’s share of income hasn’t changed much in Australia since the late 1050s. It rose for a period a little then fell back a little. Capital’s share seemed to rise quite a bit but most of that was due to the statistician’s practice of imputing rental income to resident-owned homes and increased levels of home ownership. There were some changes due to the reduction in the use of labor in the financial sector due to automation in the banks but this is rather unclear because of the difficulties of measuring financial sector outputs. Generally, there are difficulties of measuring factor returns – how do you calibrate the returns to a small business owner who employs a few people?

There are better ways of thinking about distributional issues in Australia than trying to draw strong conclusions from the functional distribution of income. Real wages have grown steadily over the past 20 years although their growth (although positive) has slowed recently. The fall in real wages that will occur over the past two years seems to be a once-off. Until recently slow growth in real wages was partly caused by high minimum wages – Australia has the highest minimum wages in the OECD at 55% of median earnings – which led to persistent relatively high unemployment. Now that unemployment has been driven to the lowest levels for decades and the immigration rate slowed due to Covid, real wage growth will pick up again.

https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2019/mar/the-labour-and-capital-shares-of-income-in-australia.html

https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BriefingBook46p/WagesDevelopments

1950s

Harry Clarke says “There are better ways of thinking about distributional issues in Australia than trying to draw strong conclusions from the functional distribution of income.”

Correct.

Even the St Louis Federal Reserve Bank agrees with Jim Chalmers about GDP… “we have to take it with a grain of salt because looking at just GDP growth doesn’t paint the whole picture” (^1)

We had a Wellbeing Framework which seems to touch on the concept of “Inequality of Opportunity” until… ” the Australian framework was scrapped in 2016 under then treasurer Scott Morrison.”.

*

Thanks to Warwick Smith for articke & links, in The Conversation today;

“Australia had a world-record 28 years continuous economic growth (^1.SLFed) before the COVID-induced recession of 2020. Did this solve all our social, environmental and economic problems? Far from it. Indeed higher incomes have caused and amplified some of those problems.”

…

“In fact, New Zealand’s Treasury, along with other international well-being budget approaches, were inspired by the well-being framework the Australian Treasury established in 2004.

“But the Australian framework was scrapped in 2016 under then treasurer Scott Morrison.

“There is now an alliance of governments who have adopted well-being approaches, includeing Iceland, Finland, New Zealand, Scotland and Wales.”…

From:

“Beyond GDP: Jim Chalmers’ historic moment to build awell-being economy for Australia

https://theconversation.com/beyond-gdp-jim-chalmers-historic-moment-to-build-a-well-being-economy-for-australia-184318

*

“Treasury’s Wellbeing Framework

Date November 2012

…

“The perspective the wellbeing framework takes is that it is the substantive opportunities open to people that matter overall.”

…

https:// https://treasury.gov.au/publication/economic-roundup-issue-3-2012-2/economic-roundup-issue-3-2012/treasurys-wellbeing-framework

*

^1. SLFed.

“Has Australia Really Had a 28-Year Expansion?”

September 26, 2019

…

“So should we use Australia as a benchmark when thinking about possible duration of expansions? If so, we have to take it with a grain of salt because looking at just GDP growth doesn’t paint the whole picture. It is important to look at per capita GDP growth to have a broader view.”

https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2019/september/australia-28-year-expansion

4 day week.

Harry Clarke says: “Labor’s share of income hasn’t changed much in Australia since the late [1950s].”.

Care to provide a dataset you are using Harry? Has labour share of income changed much from the 1970s?

The OECD disagrees.

I get to quote you a Fin Review article “Why are we all working so hard?” Harry, as this is where these data below came from.

Q: Why are we all working so hard?

A: r>g a proxy for capital wagging the policy dog.

Solution – 4 days work + better support for health and wellbeing.

“it is easy to see why the campaign for a four-day week has gained momentum” (FinRev)

*

“Why are we all working so hard?

“The intensification of work doesn’t seem to be making us richer, but it does appear to be making us sicker.

…

What can be done?

“It would be tricky to wind back the various factors that have combined to intensify work. In the absence of simple policy solutions, it is easy to see why the campaign for a four-day week has gained momentum, with a trial beginning in UK workplaces.

“If we can’t work less hard, perhaps we should just work less.

https://www.afr.com/work-and-careers/workplace/why-are-we-all-working-so-hard-20220607-p5artq

*

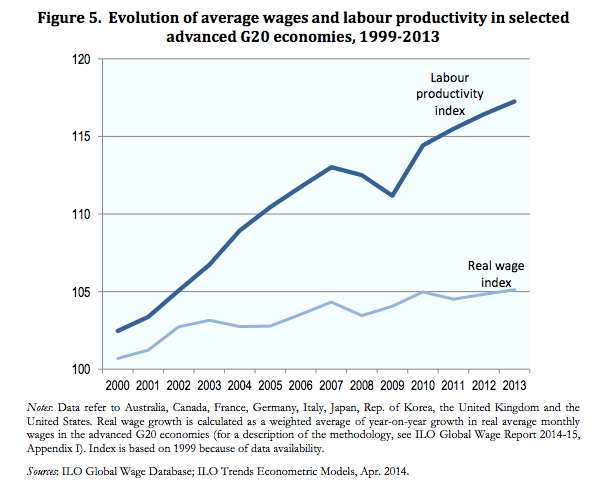

1999-2013 Avg wages and labour productivity diverge:

“Labour (wages and incomes) share of GDP

20 November 2017

by Tejvan Pettinger

…

“2. Increased retained profit

… “Substantial sums are also kept in off-shore accounts for tax reasons. Cash reserves. This increased retained profit is worrying in that it implies pareto inefficiency because they are savings which could be used to invest in more productive uses.”

“3. Increased inequality

Fall in share of labour has mirrored rising inequality”

…

https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/135320/economics/labour-share-of-gdp/

*

“The Labour Share in G20 Economies International Labour Organization

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development with contributions from

International Monetary Fund and World Bank Group

Report prepared for the G20 Employment Working Group Antalya, Turkey, 26-27 February 2015

…”wage distribution earns 25 per cent of the total wage bill while the top 10 per cent in the capital distribution owns 60 per cent of total capital, so that – ultimately – the top 10 per cent in the distribution of incomes (wages and capital) obtains 35 per cent of national income. In the U.S., these figures for the top 10 per cent are estimated, respectively, at 35 per cent for wages, 70 per cent for capital, and 50 per cent for incomes (wages and capital) (Piketty, 2013). Although not demonstrating causality, Figure 6 suggests that the decline of the labour share tended to evolve hand-in-hand with the widening of market income inequalities. Fiscal consolidation in 17 OECD countries over the period 1978 2009 has also had distributional effects by raising inequality and decreasing labour income shares (Ball et al., 2013).”

income shares (Ball et al., 2013).

“Figure 6. Changes in the labour share and in income inequality in OECD countries, 1990s to mid-2000s a

Change in the Gini coefficient for market income”

…

“If many countries simultaneously pursue policies of wage moderation (as defined by wage growth lower than labour productivity growth), the result is likely to be a shortfall in global aggregate demand, with negative effects on most countries. If this occurs within a trading bloc with close economic ties, such as the European Union, the results can depress demand throughout the bloc and beyond.”

Click to access The-Labour-Share-in-G20-Economies.pdf

KT2, The source of data is provided in the link.

Why are we hearing so much about Flu this year when the numbers are still well below 200,000 ? This is a tiny fraction of the Covid number. Because Covid has the health system stretched already. But also because flu affects children and babies most , rather than merely the expendables – the elderly ,disabled or otherwise compromised .

sunshine,

It’s misdirection. The powers-that-be and their supporters want to pretend that COVID-19 is unimportant and “over”. They are wrong of course, as they have been for the whole pandemic. In the fullness of time they will discover the foolishness of their position. Unfortunately, this foolishness is killing a lot of the innocent and vulnerable along the way. Once people start deeming other groups expendable, it is not long before they discover they too are deemed expendable. It’s a standard aspect of the descent into barbarism.