One of the strangest features of the Australian political system over the last 80 years or so has been the permanent coalition between the Liberal and National (formerly Country) parties. It sometimes puzzles foreigners – I remember an American observer saying that the prevalence of coalition governments here was an indicator or political instability. And it takes different forms in different places. At the national level, until two weeks ago, there was a standing coalition agreement even when in opposition (this dates back to the 1970s, I think). There’s a similar arrangement in NSW and Victoria, but in WA the two parties operate independently. At the other extreme are merged parties – the LNP in Queensland [1] and the CLP in the NT. In SA, Tasmania and the ACT there’s no separate country party.

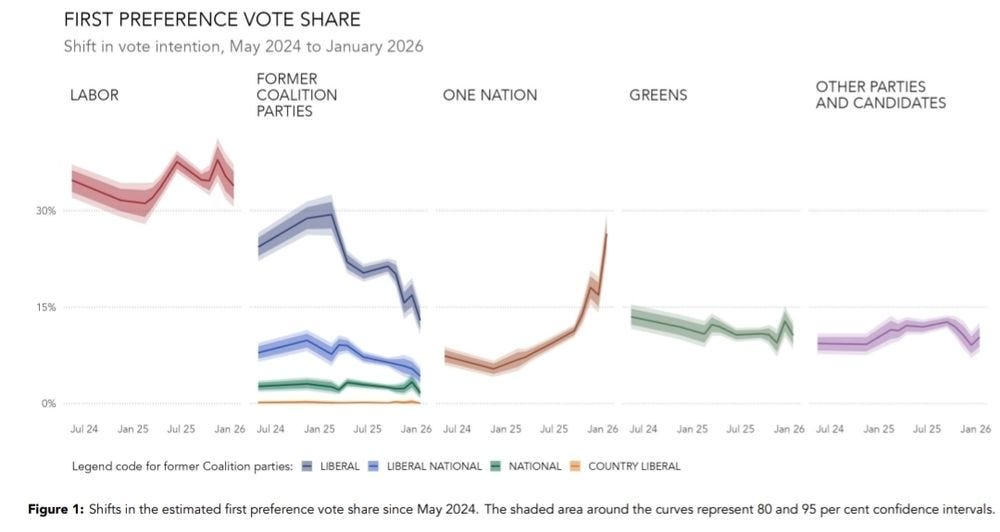

Until now, the usual convention in reporting polling results has been to aggregate these parties into a single grouping reported as “LNP” or “Coalition”. But the breakup of the federal coalition means it is better to report them separately as four groups: Liberals, Nationals, LNP and CLP. Combined with the resurgence of One Nation this yields the starting possibility that the Liberals (as well as the other three) may soon have polling support below 10 per cent.

This graph from Redbridge (kindly provide by Ben Messenger) illustrates the point. The Liberals alone were polling at nearly 30 per cent a year ago, before the 2025 election disaster, but are now barely in double digits

Regardless of the precise number, these results have dire implications for the project of a moderate centre-right urban Liberal party, split off from the rightwing and far-right majority and aiming to making some kind of common cause with community independents. Such a party would command less than half of the Liberal party’s supporters or maybe 5 per cent of the population (plus whatever it could draw from the Queensland LNP). It would start with seven or eight members in the House of Representatives, along with some Senators who would be unlikely to get a quota in a Senate election.

Of course, just about anything could come out of the current chaos. For example, a merger of One Nation and the Nationals could easily become the main opposition party. But on Hanson’s track record it probably wouldn’t last long. And even if it endured, the chance of such a party actually winning would be small. Hanson’s permanent support base (embittered middle-aged and older low-education regional voters) is not only small, but so different from the actual majority of Australians to whom they refer as “inner-city elites”.

More likely is continued division on the right, with the remaining urban seats being picked off by Labor and the independents. The dreary implication is that Labor will continue to roll up big majorities even as its primary vote falls to 30 per cent or less. And as long as Albanese is leader, those majorities will not produce any significant policy change, let alone the radical transformation this country needs to respond to the challenges of global heating, Trumpism and the information economy.

fn1. I got in trouble 20 years ago or so for a jokey post predicting that there would be no more Liberal PMs because the Libs and Nats had to merge. Happened in Queensland, but not nationally.