The culmination of Donald Trump’s state visit to the UK was a press conference at which both American and British leaders waved pieces of paper, containing an agreement that US firms would invest billions of dollars in Britain.

The symbolism was appropriate, since a central element of the proposed investment bonanza was the construction of large numbers of nuclear reactors, of a kind which can appropriately be described as “paper reactors”.

The term was coined by US Admiral Hyman Rickover, who directed the original development of nuclear powered submarines.

Hyman described their characteristics as follows:

1. It is simple.

2. It is small.

3. It is cheap.

4. It is light.

5. It can be built very quickly.

6. It is very flexible in purpose (“omnibus reactor”)

7. Very little development is required. It will use mostly “off-the-shelf” components.

8. The reactor is in the study phase. It is not being built now.

But these characteristics were needed by Starmer and Trump, whose goal was precisely to have a piece of paper to wave at their meeting.

The actual experience of nuclear power in the US and UK has been an extreme illustration of the difficulties Rickover described with “practical” reactors. These are plants distinguished by the following characteristics:

1. It is being built now.

2. It is behind schedule

3. It requires an immense amount of development on apparently trivial items. Corrosion, in particular, is a problem.

4. It is very expensive.

5. It takes a long time to build because of the engineering development problems.

6. It is large.

7. It is heavy.

8. It is complicated.

The most recent examples of nuclear plants in the US and UK are the Vogtle plant in the US (completed in 2024, seven years behind schedule and way over budget) and the Hinkley C in the UK (still under construction, years after consumers were promised that that they would be using its power to roast their Christmas turkeys in 2017). Before that, the VC Summer project in North Carolina was abandoned, writing off billions of dollars in wasted investment.

The disastrous cost overruns and delays of the Hinkley C project have meant that practical reactor designs have lost their appeal. Future plans for large-scale nuclear in the UK are confined to the proposed Sizewell B project, two 1600 MW reactors that will require massive subsidies if anyone can be found to invest in them at all. In the US, despite bipartisan support for nuclear, no serious proposals for large-scale nuclear plants are currently active. Even suggestions to resume work on the half-finished VC Summer plant have gone nowhere.

Hope has therefore turned to Small Modular Reactors. Despite a proliferation of announcements and proposals, this term is poorly understood.

The first point to observe is that SMRs don’t actually exist. Strictly speaking, the description applies to designs like that of NuScale, a company that proposes to build small reactors with an output less than 100 MW (the modules) in a factory, and ship them to a site where they can be installed in whatever number desired. The hope is that the savings from factory construction and flexibility will offset the loss of size economies inherent in a smaller boiler (all power reactors, like thermal power stations, are essentially heat sources to boil water). Nuscale’s plans to build six such reactors in the US state of Utah were abandoned due to cost overruns, but the company is still pursuing deals in Europe.

Most of the designs being sold as SMRs are not like this at all. Rather, they are cut-down versions of existing reactor designs, typically reduced from 1000MW to 300 MW. They are modular only in the sense that all modern reactors (including traditional large reactors) seek to produce components off-site. It is these components, rather than the reactors, that are modular. For clarity, I’ll call these smallish semi-modular reactors (SSMRs). Because of the loss of size economies, SMRs are inevitably more expensive per MW of power than the large designs on which they are based.

Over the last couple of years, the UK Department of Energy has run a competition to select a design for funding. The short-list consisted of four SSMR designs, three from US firms, and one from Rolls-Royce offering a 470MW output. A couple of months before Trump’s visit, Rolls-Royce was announced as the winner. This leaves the US bidders out in the cold.

So, where will the big US investments in SMRs for the UK come from? There have been a “raft” of announcements promising that US firms will build SMRs on a variety of sites without any requirement for subsidy. The most ambitious is from Amazon-owned X-energy, which is suggesting up to a dozen “pebble bed” reactors. The “pebbles” are mixtures of graphite (which moderates the nuclear reaction) and TRISO particles (uranium-235 coated in silicon carbon), and the reactor is cooled by a gas such as nitrogen.

Pebble-bed reactor designs have a long and discouraging history dating back to the 1940s. The first demonstration reactor was built in Germany in the 1960s and ran for 21 years, but German engineering skills weren’t enough to produce a commercially viable design. South Africa started a project in 1994 and persevered until 2010, when the idea was abandoned..Some of the employees went on to join the fledgling X-energy, founded in 2009. As of 2025, the company is seeking regulatory approval for a couple of demonstrator projects in the US.

Meanwhile, China completed a 10MW prototype in 2003 and a 250MW demonstration reactor, called HTR-PM in 2021. Although HTR-PM100 is connected to the grid, it has been an operational failure with availability rates below 25%. A 600MW version has been announced, but construction has apparently not started.

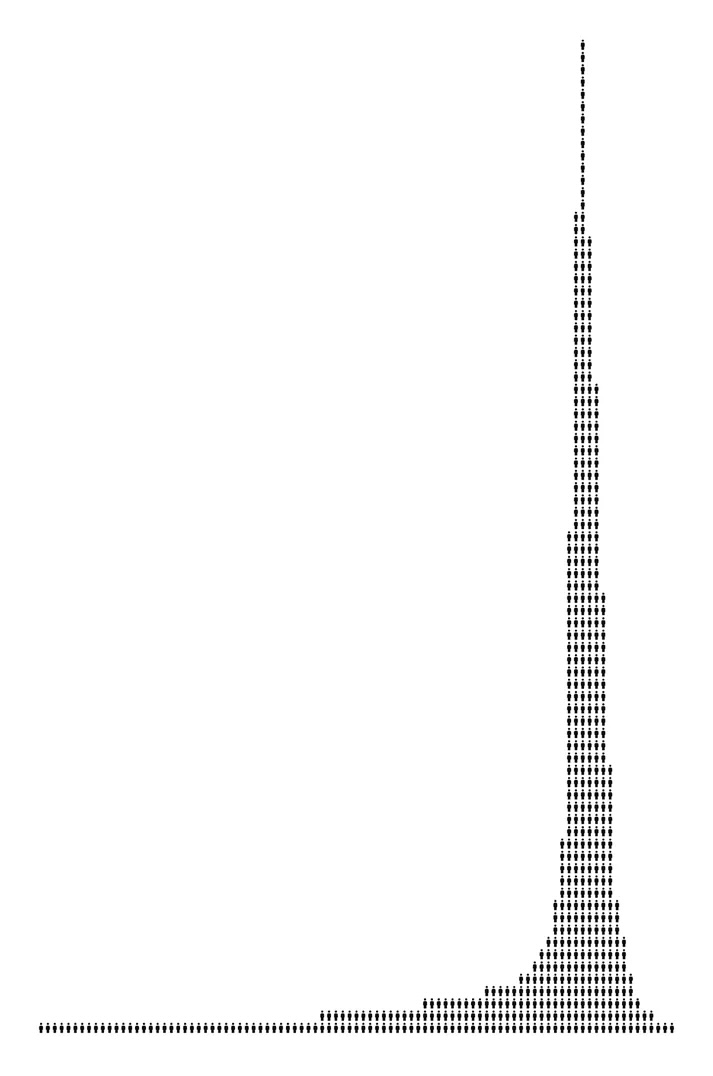

When this development process started in the early 20th century, China’s solar power industry was non-existent. China now has more than 1000 Gigawatts of solar power installed. New installations are running at about 300 GW a year, with an equal volume being produced for export. In this context, the HTR-PM is a mere curiosity.

This contrast deepens the irony of the pieces of paper waved by Trump and Starmer. Like the supposed special relationship between the US and UK, the paper reactors that have supposedly been agreed on are a relic of the past. In the unlikely event that they are built, they will remain a sideshow in an electricity system dominated by wind, solar and battery storage.