I have a letter in The Chronicle of Higher Education responding to Steven Teles’ call for more conservative college professors. It’s a shortened version of a longer piece I wrote, which I’m posting here.

The fact that conservatives are thin in the humanities and social sciences departments of US college campuses is well known. A natural question, raised by Steven Teles, is whether the rarity of conservative professors in these fields reflects some form of direct or structural discrimination.

But the disparities are even greater in the natural sciences. In 2009, a Pew survey of members of the AAAS found that only 6 per cent identified as Republicans and there is no reason to think this has changed in the subsequent 15 years. One obvious reason for this is that Republicans are openly anti-science on a wide range of issues, notably including climate science, evolution and vaccination.

The absence of Republican scientists creates a couple of problems for Teles. First, Teles’ proposed solution of affirmative action is particularly problematic here. Around 97 per cent of all papers related to climate change support, or at least are consistent with, the mainstream view that the world is warming primarily as a result of human action. The view, predominant among conservative Americans, that global warming is either not happening or is not due to human action, is massively under-represented.

The same is true across an ever expanding range of issues that have been engulfed by the culture wars. It seems unlikely that Teles would advocate enforcing a spread of opinion matching that of the US public in these cases.

Second, it is hard to see how discrimination is supposed to work here. By contrast with large areas of the social sciences and humanities, it is difficult to infer much about a natural scientists’ political views from their published work, except to the extent that anyone working in fields like biology, climate science works on the basis of assumptions rejected by most Republicans. A Republican chemist or materials scientist would have no need to reveal their political views to potentially hostile colleagues.

Economics is exempted from Teles’ criticism, but the difficulties are equally great here, though they do not fall on neatly partisan lines of conservative vs liberal. Although there are a range of views among economists on trade policy, there are almost none (with the exception of Trump’s adviser Peter Navarro) who are as sympathetic to tariff protection as the median American voter. Achieving a balance of opinion on trade policy among academic economists similar to that of the American public would require affirmative on a scale that would make Ibram X Kendi look like a piker.

But what of the social sciences and humanities? Implicitly, Teles is rejecting the view that the views of American conservatives in these fields could be wrong in the same way that scientific creationism and folk economics are wrong. If, for example, a scholar of international relations agrees with George W. Bush and the majority of Republicans that the United States is “chosen by God and commissioned by history to be a model to the world”, that should not be problem for a selection committee on Teles’ account.

The ever-expanding culture wars have contracted the areas where academic work has no direct political implications. Nevertheless, there are enough such fields that the low representation of political conservatives needs some further explanation.

Explaining the shortage of Republican scientists (and academics more generally) does not require a complex story about anticipated discrimination, like the one offered by Teles. Careers in academia require a high level of education and offer relatively modest incomes. Both of these characteristics are negatively correlated with political conservatism. The outcome is no more surprising than the fact that Democrats are under-represented among groups with the opposite characteristics, such as business owners without college degrees.

Teles caricatures such explanations as saying that “conservatives are stupid”. But he would presumably agree that an academic appointment normally requires a PhD. But PhD graduates are overwhelmingly liberal According to Pew, only 12 per cent of Americans with a postgraduate degree hold “consistently conservative” and another 14 per cent are mostly conservative. Once lawyers (JD holders) and doctors (MD holders) are excluded, there’s no reason to think that American academics are significantly more liberal that PhD graduates in general.

If so, there’s no need to invoke personal discrimination in the hiring process as an explanation for the paucity of conservatives. Rather, as Teles suggests, it seems that conservatives do not pursue academic careers in the first place.

Fear of discrimination is one possible explanation here. But a much simpler structural explanation is at hand. Compared to other high-education workers, professors have relatively modest earnings (economics, where the outside options are lucrative, is a partial exception). And controlling for education, income is strongly correlated with Republican voting. So, a plausible explanation is that intelligent young conservatives pursue careers with high earning potential in business or finance, rather than academia.

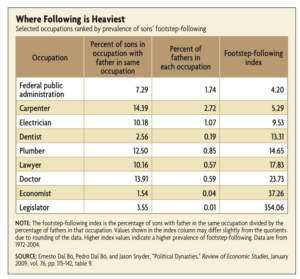

Support for this hypothesis comes from a surprising source, the medical profession. Aspiring doctors face a choice between specialisations with high economic returns (such as dermatology) and others which may yield more personal satisfaction or contribute more to public good (pediatrics).

As a New York times article about the voting patterns of doctors shows, these choices are highly correlated with voting patterns. Doctors in low-income specialisations are much more likely to be Democrats

All medical specialisations yield higher incomes than that of the average professor. But extrapolating beyond the range of the data to $75k (the average salary for full-time faculty in US universities and colleges according to Wikipedia), the predicted proportion of Republicans would be around 10 per cent, which is what’s observed in the data. A cynical interpretation is that, if Republican legislators want more conservative professors, they should pay them higher salaries, pushing them into the top tax brackets populated by corporate lawyers and orthopaedic surgeons.

As Teles observes, the disparity between the views of academics and those of the legislators who ultimately fund them is a major problem for US higher education, and ultimately for the US. But this is ultimately a reflection of the fact that conservatism, in the form it currently takes in the US, involves rejection of the intellectual values of a university.