Like most academics these days, I spend a lot of time filling in online forms. Mostly, this is just an annoyance but occasionally I get something out of it. A recent survey in which the higher-ups tried to get an idea of how the workforce was feeling, asked the question “Do you think of the University as We or They?”.

Read More »Monday Message Board

Another Monday Message Board. Post comments on any topic. Civil discussion and no coarse language please. Side discussions and idees fixes to the sandpits, please.

I’m now using Substack as a blogging platform, and for my monthly email newsletter. For the moment, I’ll post both at this blog and on Substack. You can also follow me on Mastodon here.

Monday Message Board

Another Monday Message Board. Post comments on any topic. Civil discussion and no coarse language please. Side discussions and idees fixes to the sandpits, please.

I’m now using Substack as a blogging platform, and for my monthly email newsletter. For the moment, I’ll post both at this blog and on Substack. You can also follow me on Mastodon here.

Chalmers is more in touch with the economy than the RBA

In today’s AFR. It’s paywalled and I don’t have access (I’ve been promised a PDF) so here’s what I submitted, which may not be final.

Six months ago, Federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers was planning legislation to remove his own power (never used, but always available until now) to over-ride decisions of the Reserve Bank. Now, he has not only decided to retain this power, but has openly criticised the Bank’s interest rate decisions as “smashing the economy”.

It’s easy enough to understand Chalmer’s criticism in terms of the political interests of a government seeking to survive and retain power. The government is focused, to the point of obsession, on the “cost of living”, a nebulous term that can best be interpreted as “the reduced purchasing power of household disposable income”.

Read More »Academic nepo babies

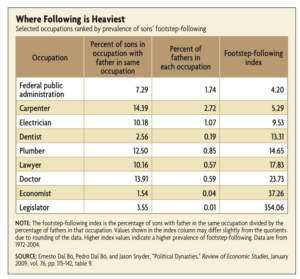

This study showing that US academic faculty members are 25 times more likely than Americans in general to have a parent with a PhD or Masters degree has attracted a lot of attention, and comments suggesting that this is unusual and unsatisfactory. But is it? For various reasons, I’ve interacted quite a bit with farmers, and most of them come from farm families. And historically it was very much the norm for men to follow their fathers’ trade and for women to follow their mothers in working at home.

So, I decided to look for some statistical evidence. I used Kagi’s AI Search, which, unlike lots of AI products is very useful, producing a report with links to (usually reliable) sources. That took me to a report by the Richmond Federal Reserve which had a table from a paper about political dynasties.

Australians should be angry about Coles’ latest billion-dollar profit. But don’t blame the cost of living

The latest massive $1.1bn profit reported by Coles will doubtless produce a new round of hand-wringing about the “cost of living”. Governments will produce initiatives aimed at capping or reducing prices. Pundits will use a variety of measures to argue as to whether such measures are inflationary. Then there will be debates about whether splitting up Coles and Woolworths into smaller chains would enhance competition. And the Reserve Bank will be encouraged to push even harder to return inflation to its target range.

But these responses, focused on the cost of goods, miss the point. Coles and Woolworths have increased their margins, yes – but prices for groceries have increased broadly in line with other goods. The real driver of supermarket profits is their ability to drive down the prices they pay to suppliers.

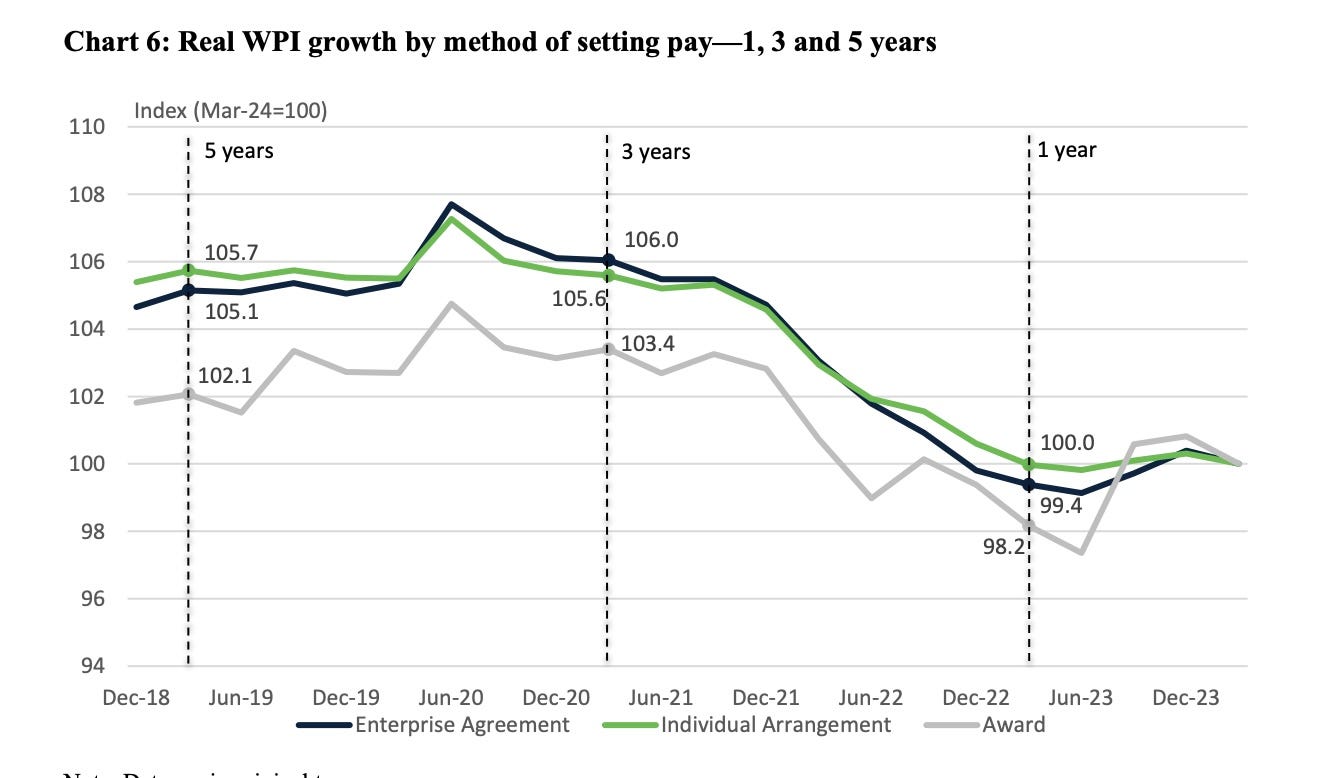

But the input that matters here is labour and it is here that the supermarkets are making big gains at the expense of their workers. Across the board, wages have failed to keep pace with prices over the last five years or more.

At least for the supermarkets, this won’t change any time soon.

In its annual wage review in June, the Fair Work Commission announced a 3.75% increase to the minimum wage and minimum award wages. But the increase barely offsets the almost identical 3.8% increase in consumer prices since the last review, leaving real wages unchanged.

Yet again, the FWC declined to do anything about the fall in real wages that has taken place since the arrival of the pandemic, compounding a long period of stagnation before that. As it noted: “Despite the increase of 5.75 per cent to modern award minimum wage rates in the AWR 2023 decision, the position remains that real wages for modern award-reliant employees are lower than they were five years ago.”

Real WPI growth by method of setting pay – 1, 3 and 5 years. Photograph: FairWork Commission

There is no cost of living crisis for those whose income derives from profits. Those at the top end of town have seen their incomes soar. But even more modestly wealthy recipients of capital income are doing well, a fact reflected in their spending patterns.

This divergence is almost invariably framed using lazy generational cliches, comparing the expenditure of older and younger generations.

To be sure, old people, such as self-funded retirees, are more likely to be receiving capital income and less likely to be reliant on wages to pay mortgage interest. But this is by no means universal. Plenty of baby boomers are still in the workforce, while some of our most prominent property owners (such as Tim “avocado toast” Gurner) are much younger. Focusing on age merely confuses a debate that is already complicated enough.

The policies of the Reserve Bank make matters even more thorny. The problems here start with a dogmatic adherence to a 2% to 3% inflation target. The rationale for inflation targeting is thin, and the choice of target range is entirely arbitrary, arising from an ad hoc decision by a right-wing New Zealand finance minister in the early 1990s, one which was followed by a long period of economic decline in that country.

The dangers of using high interest rates to achieve rapid reductions in inflation, evident from the “credit squeezes” of the 1970s and 1980s, are now becoming apparent, as the drive to reduce inflation is reflected in a push to squeeze demand and prevent any recovery in real wages.

There is little hope that all of this will change any time soon. The concept of “cost of living” is simple and intuitive, even if it is highly misleading. What really matters is the purchasing power of people’s disposable incomes. But that’s a bit too hard for our political class to think about, let alone explain to the public.

Follow me on Mastodon or Bluesky

Share John Quiggin’s Blogstack

Read my newsletter

Monday Message Board

Another Monday Message Board. Post comments on any topic. Civil discussion and no coarse language please. Side discussions and idees fixes to the sandpits, please.

I’m now using Substack as a blogging platform, and for my monthly email newsletter. For the moment, I’ll post both at this blog and on Substack. You can also follow me on Mastodon here.

Gina Rinehart’s latest grab-bag of opinions is more proof billionaires are no smarter than the rest of us

The mining magnate does away with the constraints of arithmetic, simultaneously demanding lower taxes more public spending and lower deficits

A striking feature of the age of billionaires in which we now live is that billionaires are more and more inclined to give us the benefit of their opinions. In the past year alone, we’ve had Marc Andreessen’s retro-futurist “Techno-optimist manifesto”, Mark Zuckerberg’s pronouncements on the future of media, and, most recently, a cosy chat between Elon Musk and Donald Trump (whose billionaire status is often touted but remains questionable). In most cases, the main effect has been to demonstrate that, however good they are at making money, billionaires are no smarter than the rest of us when it comes to politics or the ordinary business of life.

Australia’s richest billionaire by far is Gina Rinehart, who has massively multiplied the already substantial fortune she inherited from her father, the late Lang Hancock (Rinehart claims she inherited more debts than assets). Like Hancock, who spent decades on the rightwing fringe of Australian politics, Rinehart has never been shy about expressing her opinions.

A look at those opinions suggests that, taken as a whole, they would pass the “pub test”, in that they are about as sophisticated and intellectually consistent as you might expect to hear in the evening at a public bar. In common with many opinionators, Rinehart disdains the constraints of arithmetic, simultaneously demanding lower taxes, more public spending and lower deficits, all to be paid for by eliminating unspecified waste, fraud and duplication.

A recent piece in the Daily Telegraph, published as part of a News Corp “Bush summit” series, illustrates this point. Hancock begins with a familiar litany of woes about the high costs faced by farmers and the burden of (unspecified) red tape, forcing them off the land. This part of her article could have been (and has been) written any time in the past 50 years or more.

No one reading this sad tale would be aware that farm incomes have been at record highs last year, an outcome reflected in strongly increased land prices. The executive director of the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, noted at the time: “When you look at the cropping sector in particular, average farm incomes are about 75% above the 10-year average – about $665,000 – up slightly from last year.”

Farming is a risky business and these outcomes depended in part on a string of good seasons that came to an end this year, with farm incomes now back to where they were three years ago. But a rebound seems likely, making Rinehart’s gloomy pronouncements seem overstated, to say the least.

Turning to remedies, Rinehart wants a string of tax reductions, including the abolition of payroll tax and stamp duties along with reductions in excise tax on fuel. A striking feature of this wishlist is that most of the benefits would go to city dwellers. Few farm businesses are large enough to reach the threshold for payroll tax. Family-owned farm businesses are exempt from stamp duty on intra-family transfers, while city dwellers routinely pay tens of thousands of dollars as a cost of moving house. Finally, no excise tax is paid for on-farm (or mining) use of fuel.

These proposals aren’t matched by a willingness to accept reduced public services. After acknowledging the need for “nurses, police, hospitals, health care, our increasing numbers of elderly, emergency services and veterans (And much more)”, Rinehart goes on to demand a massive increase in provision of these services to rural areas, saying that “the Pilbara in Western Australia should have some of the best hospitals and infrastructure in the world, plus some of the best playgrounds and sports facilities”.

Some areas of public expenditure didn’t make it on to her list, but Rinehart has covered many of them elsewhere. She has been a keen proponent of publicly subsidised dams, relaxing means tests on pensions and more spending on defence (apparently to be financed by selling off the defence department’s “pot plants, paintings and sculptures”).

The closest Rinehart comes to suggesting a cut in public expenditure is a nebulous reference to handouts of “another $500m here, another $500m there”, most of which is apparently spent within the Canberra bureaucracy. Doing away with these would supposedly cover the tens of billions of dollars of reduced revenue and higher spending implied by her lengthy wish list.

And, of course, all of this is to be achieved while cutting debt and deficits, lest we share the fate of Sri Lanka and Argentina.

There’s nothing particularly unusual about Rinehart’s grab-bag of opinions. You can hear similar thoughts in any public bar (or, with minor variations, any inner-city coffee shop). But as a contribution to discussion of public policy, they are best left there.

Monday Message Board

Another Monday Message Board. Post comments on any topic. Civil discussion and no coarse language please. Side discussions and idees fixes to the sandpits, please.

I’m now using Substack as a blogging platform, and for my monthly email newsletter. For the moment, I’ll post both at this blog and on Substack. You can also follow me on Mastodon here.

Monday Message Board

Another Monday Message Board. Post comments on any topic. Civil discussion and no coarse language please. Side discussions and idees fixes to the sandpits, please.

I’m now using Substack as a blogging platform, and for my monthly email newsletter. For the moment, I’ll post both at this blog and on Substack. You can also follow me on Mastodon here.